Introduction

|

Estate regeneration in the spotlight

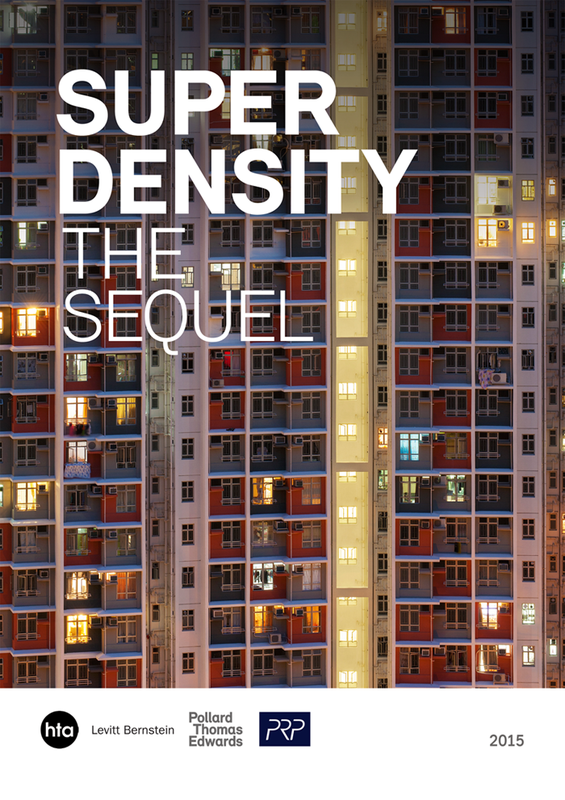

In the 1960s and 70s nearly three million homes were built by local authorities in Britain. Most of them incorporated new ideas about town planning, the design of the home and methods of construction. It is these estates which have been - and continue to be - the main focus of subsequent major regeneration initiatives, including David Cameron’s recent declaration of action on ‘sink estates’. The Prime Minister accuses the worst estates of ‘entrenching poverty in Britain - isolating and trapping many of our families and communities’. Like many observers he believes that non-traditional design is a significant part of the problem. Regeneration specialists know that the issues are far more complex, but most would at least agree that design can contribute to the social and economic success or failure of places. The four architectural practices behind this report have been involved with the regeneration of housing estates for four decades. We started to advise communities and local authorities on estate improvements soon after the last concrete panel was craned into place in the mid-1970s. Since then we have worked under successive political initiatives and funding models to improve, remodel or replace dozens of estates in London and around the UK. We have seen what works and what does not. In response to the renewed political focus on estate regeneration, this report contains a distillation of our combined experience into a series of recommendations on how best to meet the challenges of today. One intended audience is Lord Heseltine’s Estates Regeneration Advisory Panel, although our interest is broader than the government’s focus on the ‘100 worst estates’. We hope our work will also be of interest to communities, local authorities, housing associations, our developer clients and professional colleagues, including other architects who have come more recently into the challenging field of estate regeneration. Whose estate is it anyway? There is another reason why we have produced this report at this time. There has always been tension between the priority to be given to the wishes of existing residents and the potential of estates to provide a greater range of housing opportunity for the wider population, but now this has become politicised and polarised into two fiercely opposed positions. In one corner are those who believe that housing estates belong to those who live on them and only their views should count in determining the future - and increasingly their preference is to be left alone. In the other corner are those who regard housing estates as public assets, which local authorities have a right and duty to use to meet wider needs - including the growing clamor for more homes, at affordable prices, for middle-income households. The views of both camps deserve respect. Part of the reason for this polarisation is obvious to those who have been facilitating successful estate regeneration for decades: it revolves around the concept of ‘balanced communities’. A genuinely balanced community will contain a wide range of housing types and tenures for a wide range of households across the spectrum of age, ethnicity, income, occupation and household size. It will also balance the needs and aspirations of all the stakeholders, including existing tenants and leaseholders, and also ‘outsiders’ who would like to settle in the area and invest in it if only the opportunity was there. The perception of many existing residents - and their champions in parts of the media - is that estate regeneration is no longer delivering balance: the proportion of affordable to market homes is dwindling, the definition of affordability is shifting, the cost of market homes is soaring, and the buyers of those homes seem like remote aliens - far removed from being ‘people like us who have a bit more money’. They condemn estate regeneration as ‘social cleansing’ and a ‘war on social housing’. In our view it is essential that we are clear about the objective of estate regeneration: is it to improve the lives of those who live on and around existing estates, or is it to make more effective use of public land to help solve the ‘housing crisis’ by creating additional homes and widening access to home ownership? Managing and resolving this tension has been a key objective of community engagement for the past 40 years. With care, patience and respect we can and should be able to do both. We have managed it in the past, and there are many examples of successful outcomes in a set of case studies in the back of this publication. Estate regeneration and Superdensity Our last piece of collaborative work was Superdensity: the Sequel (2015), which explains how to create successful neighbourhoods at high density, and also cautions against what we call ‘hyperdensity’ - very high densities above the top end of the London Plan guidance. We focused on the importance of street-based urban design in the creation of successful mixed communities and the advantages of mid-rise over high-rise development for integration of mixed-tenures and control of management costs. All of this has become very relevant to estate regeneration. As London struggles to build enough homes to keep pace with demand, attention is increasingly turning to the regeneration of housing estates to provide more homes as well as better homes. Often estates were built to a low density, at a time when London’s population was falling, which potentially allows them to be updated in ways that create many more homes, mixed communities and a better place to live for those already inhabiting them. However, the reduction of public investment in regeneration is transforming the well-tried mixed-funding model (combining market investment with subsidy) into an increasing reliance on market-driven solutions. This means that the provision of new affordable homes on estates is becoming mainly or entirely dependent on cross-subsidy from homes for sale. Therefore, densities are being pushed up to create enough surplus income - with the risk that some outcomes breach our guidelines for successful superdense development and could be unsustainable in the long-term. At the same time, other forms of low cost housing like shared ownership have moved out of reach for those on low incomes. These market-led developments, at a time of welfare cuts and depressed wages, all add to the perception that existing communities are losing out. No banlieues please - we’re British We hold to the principle that our cities prosper best as places if we encourage the integration of mixed communities within them. Indeed, it is the essentially democratic and fair distribution of people from all walks of life, and the idea that citizens have free access to all areas on streets that are policed by consent, that has endowed Britain with enduringly popular and peaceful cities. Putting low cost housing at the heart of revitalised estates is a key demonstration of this principle. Established cities go through cycles of decline and renewal, often without the benefit of any organised intervention. Sometimes urban pioneers colonise run down and low cost areas, creating a hipster brand that generates value. Sometimes environmental blights vanish, such as when electric propulsion replaced steam, lifting the smog from around the marshalling yards of Camden Town. Gentrification is neither sensitive nor fair, but it is an established and inevitable form of urban renewal and its effects can be dramatic. In the span of two generations the areas in the so called ‘inner ring of multiple deprivation’ in London have evolved into some of the most desirable neighbourhoods. This has happened almost entirely as a consequence of private investment in property, albeit with a following wind of fiscal subsidies to support the process. In our work, we seek to avoid the creation of neighbourhoods that are exclusive to either the rich or the poor. We believe instead that people from all sectors of society thrive and prosper best with equal access to the benefits of urban life and the opportunity to interact with each other both socially and economically. The dilution of concentrated social deprivation, and raising the overall economic activity in an area, are good things, even though there is a lack of evidence to prove that estate regeneration improves the social mobility of the poorest people. In his study of mixed communities in England, Alan Berube of the Brookings Institute in Washington summarised the key disadvantages of neighbourhoods of concentrated deprivation:

Finally, we recognise the importance of the democratic process employed to plan and deliver any major project of urban regeneration. Planning, masterplanning and urban design must deliver better and more sustainable living environments, but there will be cost, disruption and disappointment for some. Planning is the democratic process that legitimises the disadvantage suffered by a minority in favour of benefits for the majority. It is thus imperative that processes of regeneration are transparent and organisations are properly accountable for the decisions made in their name. Focus on London We acknowledge that this report is focused on London and the South-east, where land values and house prices bring their own solutions and problems - a markedly different financial equation compared to what is possible with estates in south Yorkshire or the North-east, for example. However, our practical guidance for essential processes like options appraisal, urban design and engaging with communities are not location-specific, and will, we hope, be useful to those involved in estate regeneration throughout the UK. The structure of this report Our report is arranged into four chapters followed by a set of case studies. Chapter 1 Appraising the options explains how a methodical and transparent process of options appraisal can assist selection of the best regeneration strategy and lay the foundations for effective community engagement. Chapter 2 Engaging communities sets out best practice in stakeholder engagement leading to community buy-in and avoiding top-down imposition of unpopular proposals. Chapter 3 Getting the design right addresses the sensitive issue of re-integration of estates into the surrounding townscape and confronts the limits of high density intensification. Chapter 4 Achieving sustainable outcomes tests some of the conclusions in the previous chapters against long-term measures of sustainability and explains why current government policies require review if unsustainable outcomes are to be avoided. Each chapter concludes with some concise recommendations. The practices have selected 12 case studies to illustrate the range of estate regeneration initiatives over the years and include a number of current live projects. The case studies cover most of the key government programmes and funding models, including the Single Regeneration Budget (SRB), Estates Renewal Challenge Fund (ERCF), Private Finance Initiative (PFI) and others. They range from fully grant-funded programmes like Estates Action and Housing Action Trusts to private equity models for council housing, requiring no grant or cross-subsidy. Most involve some form of mixed private and public funding. What next? Our report is only the beginning of this project. We have sought funding and we hope to go on to research the consequences of the schemes in which we have variously played a part, and carry out post-occupancy research into the experience of populations in the neighbourhoods affected. We see a pressing necessity that the designers and developers of such projects should build up a body of evidence about the consequences of their contribution to urban regeneration. |

Altered Estates report 2016 click here to download

Contents of the report

Foreword, Lord Kerslake Introduction Recommendations Chapter 1 - Appraising the options Chapter 2 - Engaging communities Chapter 3 - Getting the design right Chapter 4 - Achieving sustainable outcomes Appendix Superdensity: the Sequel report 2015 click here to download |